HTTP Protocol Tutorial

In 10 minutes, you'll have a basic understanding of HTTP protocol.

Here's a summary of what HTTP protocol is:

- A Client/Server model.

- Request/Response. Client makes a request to a server, server responds.

- Request typically is over TCP, at port 80. 〔see TCP/IP Tutorial for Beginner〕

- Request/response format is just plain text, of two parts, header and payload (content), separeted by a empty line.

- First line of request message is called request line. It contains the “command”.

- First line of response message is called status line. It contains the “status code”.

- There are different “commands”, technically called “request methods” . Most useful are GET and POST. GET basically just ask for a resource (for example a file, or any data identified by a path.) POST means sending some data to server, such as needed by login or shopping chart.

- Each response has a status code.

For example, when you use web browser to view a URL, the following happens:

- Browser send a request to a server. (Server address is contained in the URL.)

- The server sends back response, also plain text. (if it is image file, the image is encoded into text.)

- The browser renders the result. (if it is HTML, browser parses it, and may make other requests such as images, style sheet, JavaScript file, etc.)

To understand HTTP protocol, we just need to understand the HTTP messages that the client/server send. Let's first look at tools to view HTTP messages.

How to See HTTP Messages

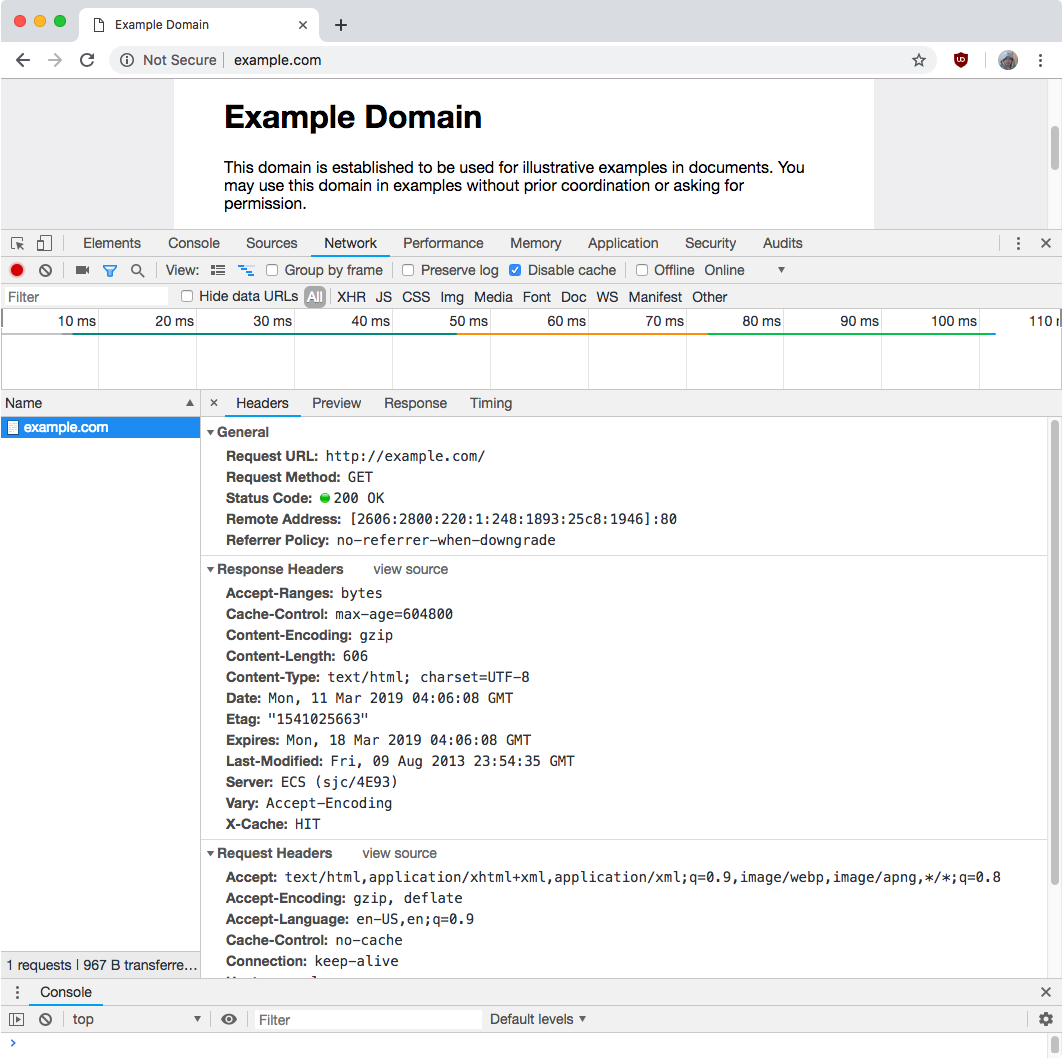

See HTTP Headers in Web Browser

you can use web browser to view the header sent/received by client/server.

Here's how to use Google Chrome to view HTTP messages:

- Open the web development tool. (in Google Chrome, press F12 on Windows or Linux. Other browsers/OS have similar tool. You can find it in their menu.)

- Click on the Network tab.

- Visit some page, type a URL in the URL box and press Enter.

- Click on a item in the left of the network report, to see the HTTP message header for that item. (each item is a HTTP request made by browser.)

Linux Command to View HTTP Headers

The following command line tools can view HTTP response header.

curl --head example.comwget --server-response --spider example.com

Here's curl example:

curl --head example.com HTTP/1.1 200 OK Accept-Ranges: bytes Cache-Control: max-age=604800 Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8 Date: Mon, 11 Mar 2019 04:25:57 GMT Etag: "1541025663" Expires: Mon, 18 Mar 2019 04:25:57 GMT Last-Modified: Fri, 09 Aug 2013 23:54:35 GMT Server: ECS (sjc/4E4E) X-Cache: HIT Content-Length: 1270

Here's wget example:

wget --server-response --spider example.com Spider mode enabled. Check if remote file exists. --2019-03-10 21:29:03-- http://example.com/ Resolving example.com (example.com)... 2606:2800:220:1:248:1893:25c8:1946, 93.184.216.34 Connecting to example.com (example.com)|2606:2800:220:1:248:1893:25c8:1946|:80... connected. HTTP request sent, awaiting response... HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Encoding: gzip Accept-Ranges: bytes Cache-Control: max-age=604800 Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8 Date: Mon, 11 Mar 2019 04:29:03 GMT Etag: "1541025663" Expires: Mon, 18 Mar 2019 04:29:03 GMT Last-Modified: Fri, 09 Aug 2013 23:54:35 GMT Server: ECS (sjc/4E45) X-Cache: HIT Content-Length: 606 Length: 606 [text/html] Remote file exists and could contain further links, but recursion is disabled -- not retrieving.

〔see Linux: wget (Download Web Page)〕

Other languages, such as Python and Ruby, have similar tools or libraries.

Client/Server Messaging

Sample message sent by client:

GET /hello.txt HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: curl/7.16.3 libcurl/7.16.3 OpenSSL/0.9.7l zlib/1.2.3 Host: www.example.com Accept-Language: en, mi

Sample message sent by server:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Mon, 27 Jul 2009 12:28:53 GMT Server: Apache Last-Modified: Wed, 22 Jul 2009 19:15:56 GMT ETag: "34aa387-d-1568eb00" Accept-Ranges: bytes Content-Length: 51 Vary: Accept-Encoding Content-Type: text/plain Hello World! My payload includes a trailing CRLF.

Lines in HTTP message must be separated by the character sequence "\r\n".

(that is, a carriage return followed by a line feed. Yes, both.)

〔see ASCII Characters〕

The message exchanged by client/server is plain text. It has 2 parts, header and content.

Header and content are separated by 1 blank line.

The first line of the header is special.

If it's request, it's called request line. For example, it looks like this:

GET /tutorial/index.html HTTP/1.1

If it's response, it's called status line. For example, it looks like this:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

The rest of header part is made of lines, each line is called a “field”.

A field is separated by first colon : into two parts: field-name and field-value.

HTTP Methods

Recall that the first line of request looks like this: GET /tutorial/index.html HTTP/1.1

It has 3 parts: (1) request method. (2) resource path. (3) http version.

The most used request methods are:

- GET

- Request a resource.

- HEAD

- Same as GET, but only get headers, no content. That is, just request metadata. Useful for web crawler, proxy server, etc.

- POST

- Send some info to server. For example, used for login, credit card, shopping cart, via HTML Form. 〔see HTML Form Example〕

Other methods are much less used , and may not be implemented by server.

The following is a more complete list from HTTP/1.1 (source is Wikipedia 2019-03-11)

- GET

- Requests a representation of the specified resource. Requests using GET should only retrieve data and should have no other effect. (This is also true of some other HTTP methods.) The W3C has published guidance principles on this distinction, saying, “Web application design should be informed by the above principles, but also by the relevant limitations.” See safe methods below.

- HEAD

- Asks for a response identical to that of a GET request, but without the response body. This is useful for retrieving meta-information written in response headers, without having to transport the entire content.

- POST

- Requests that the server accept the entity enclosed in the request as a new subordinate of the web resource identified by the URI. The data POSTed might be, for example, an annotation for existing resources; a message for a bulletin board, newsgroup, mailing list, or comment thread; a block of data that is the result of submitting a web form to a data-handling process; or an item to add to a database.

- PUT

- Requests that the enclosed entity be stored under the supplied URI. If the URI refers to an already existing resource, it is modified; if the URI does not point to an existing resource, then the server can create the resource with that URI.

- DELETE

- Deletes the specified resource.

- TRACE

- Echoes the received request so that a client can see what (if any) changes or additions have been made by intermediate servers.

- OPTIONS

- Return the HTTP methods that the server supports for the specified URL. This can be used to check the functionality of a web server by requesting ‘*’ instead of a specific resource.

- CONNECT

- Converts the request connection to a transparent TCP/IP tunnel, usually to facilitate SSL-encrypted communication (HTTPS) through an unencrypted HTTP proxy. See HTTP CONNECT method.

- PATCH

- The PATCH method applies partial modifications to a resource.

For detail about the commands, see:

- RFC 7231 HTTP/1.1: Semantics and Content

- By IETF.

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7231

HTTP Status Code

HTTP Cookies

Cookies is also sent as part of the HTTP header.

What is a cookie?

Basically, when server responds, it can return a header such as

Set-Cookie: name=value.

When browser sees that, the browser is required to store it locally, along

with which server the cookie came from. When browser makes a request to

a server, browser must also send all cookies that the same server sent

before.

The purpose of cookies is for server to keep states of clients. For example, by setting a cookie, the server is able to know if the browser user is logged in.

For detail on how cookies work, see:

The TCP/IP Protocol Suite

The HTTP protocol is a high-level application layer protocol of the TCP/IP internet protocol suite. HTTP protocol is about client/server exchanging messages.

But how exactly do browser find server across the globe? and How does browser send message exactly, by airplane?

The details of how client/server communicate, is specified by many lower protocols in TCP/IP. For a basic introduction, see TCP/IP Tutorial for Beginner .

Reference

- RFC 7230, HTTP/1.1: Message Syntax and Routing.

- RFC 7231, HTTP/1.1: Semantics and Content.

- RFC 7232, HTTP/1.1: Conditional Requests.

- RFC 7233, HTTP/1.1: Range Requests.

- RFC 7234, HTTP/1.1: Caching.

- RFC 7235, HTTP/1.1: Authentication.

- RFC 2817 Upgrading to TLS Within HTTP/1.1.

- RFC 5785 Defining Well-Known Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs).

- RFC 6266 Use of the Content-Disposition Header Field in the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

- RFC 6585 Additional HTTP Status Codes.

- HTTP State Management Mechanism

- By IETF.

- http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6265

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol Version 2 (HTTP/2)

- By IETF.

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7540

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol -- HTTP/1.1

- By IETF.

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2616